Published by The Lyons Press, 2006.

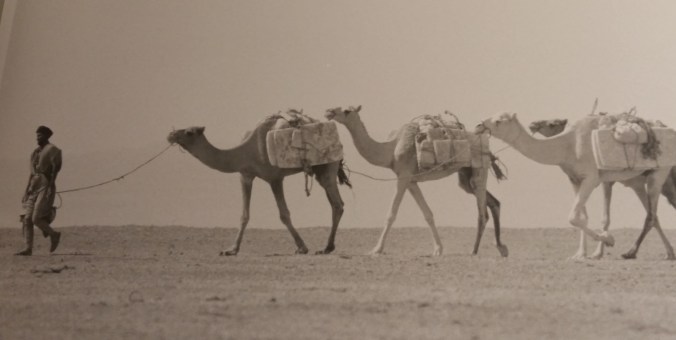

Caravan returning from the salt mines of Taoudenni © Alistair Bestow

opening lines:

“The boat coasted slowly into the port at Kourioume, on the Niger River, manoeuvering its way into an open space among the other wooden crafts already moored there. It was ten o’clock on a late-October night. Only a few scattered lights glowing in the houses on shore broke the total darkness. The air was hot and still except for the faint wakes stirred up by circling swarms of mosquitoes.”

…

The words ‘Timbuktu’ and ‘the Sahara’ often conjure mythical notions of far-away locations in the Western psyche. For many of us these places will remain unexplored – both literally given recent troubles in this part of Mali, but also figuratively. This is why Michael Benanav’s book is so valuable; we learn about a part of the world and way of life not many of us are aware of. The author, a journalist and photographer with a deep passion for nomadic desert peoples but well aware of his outsider status as a Jewish American, takes us with him as he travels from Timbuktu to the salt mines of Taoudenni with the salt caravans, and back again. Along the way he muses on the fascinating history of these landscapes and their people, and describes the personal highs and lows of his travels.

Timbuktu was a former trading hub near the banks of the Niger River, made rich by salt, ivory, gold, and slaves in an era when the trans-Saharan trading network was at its peak. At the same time, it experienced a golden age as a centre for Islamic learning. However Moroccan invasion in the 17th century signalled the start of Timbuktu’s decline, and today it is an impoverished town threatened with desertification. Part of the title of this book, ‘the caravan of white gold’ refers to the salt the camels carry, which used to be very valuable indeed; Benanav suggests that salt was once worth its weight in gold, and was used as currency until French colonisation in the 1890s introduced paper money.

One of the delights of this book is how Benanav delves into the ways of these desert people; I particularly enjoyed learning about their language. Another delight is the camels, and I have a complete newfound appreciation, respect and admiration for these animals. Those drawn to deserts will identify with many passages in this book. For me, it was the quality of light in day and night, and the sand. Sand has a special way of permeating everything in the desert – food, drink, hair, pores, sleeping gear – nothing is sacred. And the wonderful remoteness deserts offer, away from modern comforts and certainty and the tamed landscapes of farms and cities; all that expanse of time and space without distraction…and of course the challenge remoteness presents for storing food on long desert journeys – in this case, rancid goat butter and goat meat!

This book wins points for including maps (a necessity given I suspect many readers wouldn’t know where Mali is, let alone where Timbuktu or Arouane are) and a reference list. Despite all this I did have a few quibbles with the book. I wanted to know more of the author and his background, what it was that motivated the author to seek out desert peoples around the world and document his experiences. I also could not agree with him on some of the topics he was confronted by, such as child marriage, and while I can see he was trying to avoid cultural imperialism in his rationale for justifying such practices, I was not convinced. And finally, while a superb narrative of his experience, for some reason I found his writing didn’t connect with me the way other travel literature often does.